On Art and Humanity

When the film ended, we talked about what we’d seen in the way you would with anything that fascinates you, a thing that urges you to look again.

I’ll start this thing by saying you need to see Inglorious Basterds, a film made by Quentin Tarantino in 2009, if you haven’t already. The movie offers an alternate history set in France during World War II. It has moments that are profound, and moments that are profoundly funny. The best character in the movie might be Brad Pitt as Lieutenant Aldo Raine. Aldo Raine, an American soldier, is peak comedy, and he’s not always subtle.

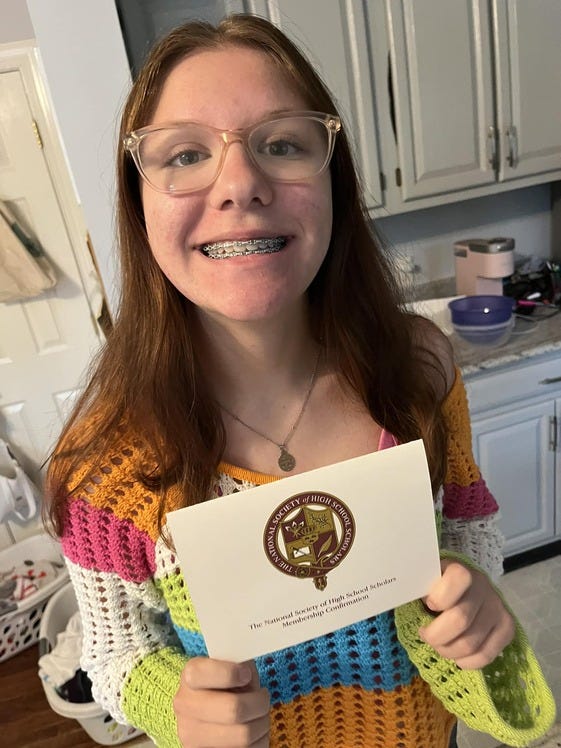

It's not an exaggeration to say Inglorious Basterds is held in high regard here at the homestead, and that’s best illustrated by sixteen year old Macey who has seen the film at least nine times by her own count. Some parents don’t want their kids to watch R-rated movies, but I trust my own judgement because I trust that the girls in my house can handle whatever might happen on the screen. Besides, Macey is a student of history, and the way Tarantino flips the story of European Jews on its end is beyond worthwhile. Inglorious Basterds is a curse-fest, too, which probably contributes to its rating, but people—including me, a lot—curse in real life and that’s not a thing I need to hide from my daughters.

If I do have questions about my perceptions, they’re related to the end result of watching a movie like this—what happens after the fact. Macey first watched Inglorious Basterds with me. I’d seen it before (more than once) and it was one of those You have to see this moments. From the first scene it was obvious that she liked it a lot. When the film ended, we talked about what we’d seen in the way you would with anything that fascinates you, a thing that urges you to look again—the conversation that happens after any performance or movie or show that makes you feel something.

That’s what great art is supposed to do—it forces you to stop and consider what you’ve just absorbed, to think and have discussions about meaning and whatever judgments you’ve rendered, and to remember scenes that hit hardest. It’s the same thing that makes you stare at a painting or a photograph or listen to a song a second or third time; it’s a feeling that can’t always be articulated.

If you’re Macey, you might also memorize and perform the two-minute scene from the movie where Aldo Raine introduces himself to the Jewish American soldiers he leads through France. Yes, that’s what my daughter did, and it makes me proud and happy. Why? It’s a great piece of filmmaking, and an exceptional example of how a monologue can effectively introduce a character. In this case, after two minutes we know exactly who Aldo Raine is.

What I should probably say next is this: I’m not surprised that Macey has watched Inglorious Basterds nine times, and I disagree with the mother of one of her friends who found it “weird” that a teenage girl would be obsessed with a film about World War II. I’m not surprised that Macey can recite Aldo Raine’s speech (and mimic his accent) like the words were her own. I don’t think any of this is weird at all because there are movies I’ve watched nine times, and books I’ve read nine times, and albums I’ve listened to nine-hundred times (or more).

All of my kids are like me in one way or another, and this is a discussion I’ve had with Macey. The two of us are obsessive when it comes to art, and when we encounter something that touches us, we must return to it again and again—and we do.

If I’m to make this behavior reasonable or logical, I suppose I can—by saying art holds mysteries and we need to understand them. And maybe we can’t understand them, or won’t, but the idea is to keep trying. Obsession and repetition like this are not ill-advised or strange. In fact, I would contend that this tendency to revisit any work of art is a sure sign that my daughter and I are alive and well!

Through that art, we are connected to every mystery that makes us human, connected in a way that’s profoundly important. I might ask if there’s any activity that’s more important or noble than trying to understand your humanity since, as Aldo Raine might say, it’s a goddamn complexity and it needs to be considered from every fuckin’ angle. Besides, it’s pretty funny when Macey does Aldo. It’s very, very funny.

And if you’ll excuse me, I’ll stop writing now since I have a list of things to watch, read, and listen to—again. There’s work to do.